A FIRE STORY (now with a Q&A with Author Brian Fies)

How I Met Brian Fies and How the First SerioComics of Year 2 Finally Got Its Q&A!

After Year One of SerioComics.

When I shared enthusiasms for 52 works of graphic literature.

I decided Year Two would include Q&As with the creators behind each featured work.

SerioComics #53 kicked off Year Two with my own debut, Should We Buy A Gun?

SerioComics #54 followed with A Fire Story by Brian Fies.

In response to the LA fires at the time.

Since then…

SerioComics #55 through #70.

Every post has included a Q&A.

But it’s always stuck in my craw that the very first post of Year Two didn’t.

So last week, I reached out to Brian Fies.

And in true generous form, he responded…

With a deeply thoughtful, expressive Q&A.

Which I’m honored to share with you all for Father’s Day weekend.

A true father of the seriocomic graphic memoir form…

Brian Fies

Brian Fies is an acclaimed American cartoonist known for his deeply personal and historically resonant graphic novels. His groundbreaking work Mom’s Cancer was the first webcomic to receive an Eisner Award, winning Best Digital Comic in 2005. The book also earned him a Harvey Award for Best New Talent and the Lulu Blooker Prize, with its German edition receiving the Deutscher Jugendliteraturpreis (German Youth Literature Prize) in the Non-Fiction category.

Fies continued his success with The Last Mechanical Monster, an Eisner-nominated graphic novel, as well as Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow?. His powerful webcomic A Fire Story, chronicling the destruction of his home in the 2017 California wildfires, was expanded into a full-length graphic novel and widely praised for its raw storytelling. In recognition of his contributions to comics, Fies was awarded an Inkpot Award in 2018.

A FIRE STORY

Early on the morning of Monday, October 9, 2017, wildfires burned through Northern California, resulting in 44 fatalities. In addition, 8,900 structures, including more than 6,200 homes, were destroyed. One of these homes belonged to author and illustrator Brian Fies of Mom’s Cancer.

In the days that followed, Fies hastily pulled together a firsthand account of his experience in a twenty-page online comic, entitled A Fire Story, that went viral…

Less than a year after the fire, Brian Fies expanded his webcomic into a full-length graphic novel, including environmental insight and the stories of others affected by the disaster.

And then added to it a third time for an expanded edition.

As he did with Mom’s Cancer, Fies has taken tragedy and created art, illuminating his experience and crafting his story to make it universal.

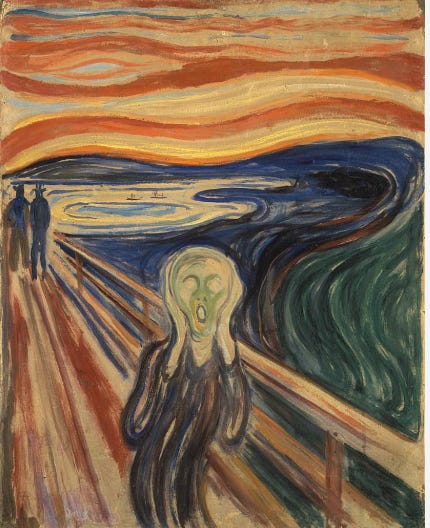

Expressionistic

As we’ve seen with some of the coverage of the Palisades and Eaton fires this month, there have been a lot of direct video recordings of the fire.

But Fies’ account shows the expressionism of the fire, which conveys some of the emotionality of its effects.

And harkens back to German Expressionism.

Informative

Fies’ book is also very detailed and helpful in providing information about what happens if this happens to you.

But he does this in a digestible, relatable, and story-focused way.

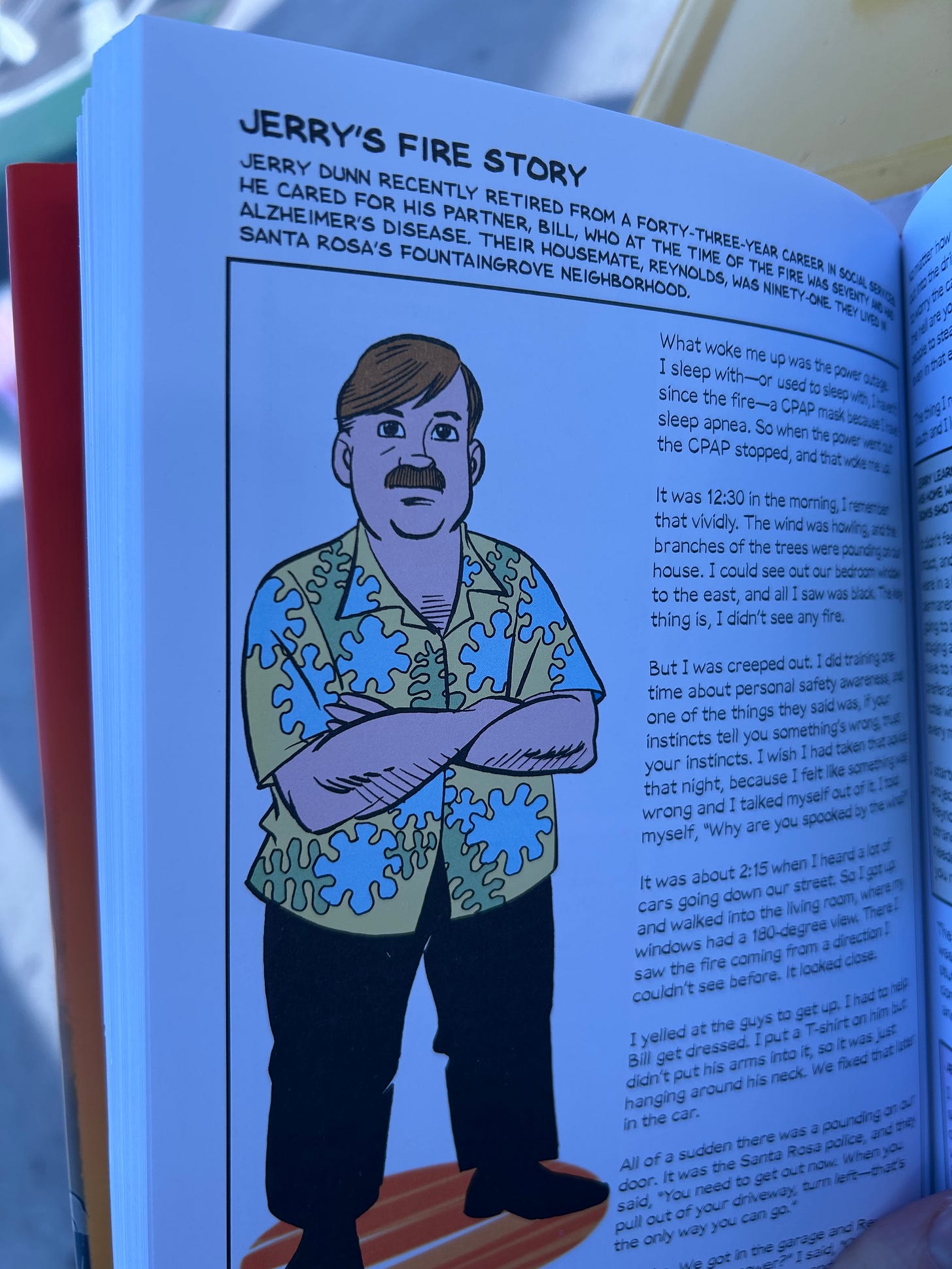

Other Fire Stories

One of the most surprising yet effective elements of Fies’ graphic novel is how he includes throughout the book two-page layouts of other peoples’ fire stories.

These break up the narrative to provide a diversity of views of the situation and outcomes of the experience.

How A Fire Story Applies To Should We Buy A Gun?

I think both my book and A Fire Story have that unfortunate/fortunate quality of being endlessly potentially timely.

But they both allow us to learn from these perennial problems.

Something that I might have considered from Fies’ work was his breaking up of the story with other semiautobiographical or autobiographical gun stories.

Update

I have indeed started to film some of these other people autobiographical gun stories.

Here’s one.

And here’s another.

OK, without further adieu…

The Q&A with Brian Fies!

1. SerioComics: I wrote about your graphic memoir A FIRE STORY as the first SerioComic enthusiasm of year two right after the fires in Altadena and the Palisades here in LA. Have you seen a renewed interest in your work from others as well?

Brian Fies: Thank you for including my book in your SerioComic series!

A FIRE STORY has remained sadly relevant following my own firestorm in 2017. Since the graphic novel was published, I’ve talked to people who’ve faced similar and worse fires in Colorado, Oregon, Washington, Hawaii, southern California and elsewhere. I’ve given talks all over the western United States, and we all share the same story. Historically destructive blazes are happening everywhere, nearly every fire season.

That experience changed my perspective. When I began working on A FIRE STORY two days after my neighborhood was destroyed, I regarded our fire as a one-off: one of those freak once-a-century disasters that happens every now and then. At the time, my Tubbs Fire was the most destructive in California history. A year later it was eclipsed by the Camp Fire, which destroyed twice as many homes and killed twice as many people. A record like that shouldn’t be broken every year. I now regard A FIRE STORY as an early contribution to the literature of the impact of climate change on individuals and communities.

My experience as a creator is that following each major blaze somebody says, “Hey, you all should go read this, it’s about what we’re going through right now.” That makes me happy because A FIRE STORY lets the survivors know that they’re not alone, and gives them some inkling of what’s to come; it makes me sad because it seems like it will always be necessary.

2. SerioComics: You mentioned in your email that I was one of the few who wrote about your use of expressionism in the art style to convey what it FELT like rather than what it just actually looked like, can you share more about this art style and why it was so important in this work?

Brian Fies: Among the tremendous strengths of comics as a medium are their ability to express emotion and invoke empathy. A single black panel can speak volumes, as can a single blank one. A simple black line can make a reader laugh or cry. Something about the combination of words and drawings bypasses some of the analysis and interpretation the mind has to employ when reading text. A well-crafted comic can feel like telepathic communication between an author and reader.

A comic is not an accurate record of an experience or event. Rather, comics distill reality to its essence. Cartoonists start with reality and then pare it down, sanding and polishing, until they get to one gem of an idea they want to communicate as clearly and directly as possible. Even before A FIRE STORY, I often said that if you want to know what happened at an event, you’d watch a video of it; if you wanted to know what it felt like, you’d read a comic about it.

I could make up a fancy analysis of my art style, but the fact is that most of my creative decisions boil down to “It seemed like a good idea at the time.” Part of my style in A FIRE STORY honors the original 18-page webcomic I drew and posted right after the fire, which I made with felt-tip pens and four colored highlighters. The art was sloppy, but also had an urgency and immediacy from being done on the spot and in the moment that I liked. Consequently, the graphic novel has a very limited palette of, I think, six or seven colors that I applied to look as if they’d been done with highlighters. That lends itself to big swipes and swoops of overlapping color that I think has an evocative look.

I’m glad you picked up on the Expressionistic influence. I never set out to “do” Expressionism, but I did want to capture the subjective experience of seeing the situation through my eyes, which I think is what Expressionism is all about.

3. SerioComics: I loved the other people’s fire stories interludes, can you tell us more about how you came to insert that device, what the process was of interviewing those people, and what it’s like publishing their life story in a way?

Brian Fies: When I set out to make the graphic novel, I really wanted it to stand as a work of journalism. My first job out of college I was a reporter for a small daily newspaper, and I realized I’d stumbled into the middle of a big story. I saw my job as something like a war correspondent reporting from the front lines. I wanted to tell people “out there” what was happening “in here.”

So with the book I wanted to tell a broader story than simply reporting what had happened to me. I wanted to give some environmental context to it, talking about California’s geography and droughts. I also wanted to tell other people’s fire stories: people who were richer and poorer than me, people who lived in different places and had different experiences. The sad thing about surviving a disaster is that you can hardly throw a rock without hitting someone with an interesting story. Some of the subjects were friends and neighbors of mine. One, Dottie, had been mentioned in a newspaper article. I found Sunny, the construction worker, when he was driving an excavator down my block and sat down for a break. In each case, I recorded an interview with the subject and made sure they understood what I intended to do with it.

Some people have asked why I published those other people’s fire stories as text rather than drawing them as comics. I decided to tell their stories in words because that’s how they told them to me. If they’d been cartoonists and had drawn their stories, I would have published those (in fact, I’d hoped to publish a two-page story by a cartoonist pal but we just couldn’t make it happen). I also didn’t feel like I could have drawn their stories honestly because I wasn’t there. I didn’t see what they saw. I respected their first-person accounts enough to not want my interpretation of their words to muddy them.

They are my favorite part of the book and I think they add a lot.

4. SerioComics: Your book really captures the long tail of this devastation, here in LA, parts of the city and much of the world have already moved on, yet your book shows how much there is to process emotionally and accomplish logistically after a fire. This work started in the immediacy of the event as a short webcomic but became a full book, how did you know when you had enough perspective for the book versus the comic?

Honestly, I didn’t. One review that sticks in my craw said I should have waited a year or two before writing the book to achieve a more balanced perspective. But that wasn’t the point. Again, I saw myself as a war correspondent on the front lines. That job is about first-person experience in the moment. Let the historians provide perspective. My urgency was just to get it out as quickly as I could, before everyone had moved on and forgotten about it.

The webcomic ended when my family and I were out of immediate danger. The hardcover book ended with my property being cleared, which was a real emotional and practical turning point. Once a bulldozer has scraped every trace of your house off the earth, there is no more hope that someday you’ll turn over a stone and find a lost piece of your old life. It’s all finally gone, and you have no direction to face but forward. When the paperback book came out a year later, I added 32 new pages that talked about rebuilding our home and facing the threat of another wildfire. It provided another natural bookend. By the way, that “updated and expanded” paperback version is the one I’d recommend to your readers!

5. SerioComics: Trauma is a potent source of art making, we process things individually that can ultimately help the collective. Can you speak to why you felt called to tell your Mom’s Cancer story and then A Fire Story in this way, and give advice to other art makers about how to alchemize painful life into healing art?

I wrote my first webcomic and graphic novel, MOM’S CANCER, because I wanted to leave a roadmap for others braving the mysterious and uncharted land of cancer behind us. My family and I were repeatedly blindsided by interactions with the medical community that no one had prepared us for and we had no way to anticipate. At the time, I wasn’t sure how I wanted to tell our family’s story until one day I drew a sketch of my mother getting chemotherapy, and realized in that a single drawing with words—a cartoon—I captured more about what that day was like than I could have in a thousand words. So I decided to do it as a comic, which I put online where it went viral and led to my modest career as a cartoonist.

During our fire, even before I knew my home had been destroyed, I knew I’d be reporting it in the form of a comic. MOM’S CANCER had given me the template; I knew that a comic could handle a serious nonfiction story about struggle and trauma. I followed pretty much the same playbook: a webcomic that went viral and then became a book.

I knew they could both work for the reasons I described earlier: the marvelous ability of comics to put readers firmly in the characters’ shoes. You see what they see, think what they think, feel what they feel.

My advice to other art makers sounds stupidly obvious but is hard in practice: be honest. Tell the truth. Readers want authenticity and can tell when you’re faking it. The best review you can get is when a reader says they thought or felt the exact same thing but had no idea anyone else did. You might have to dig a little deeper to earn that response.

6. SerioComics: Lastly, what can we expect from you next, who has influenced you, and who else should we be reading?

I am always working on something! I’ve finished one long-form comic that I hope will see print somehow someday. If not, it may find a home online.

Next year is the 20th anniversary of the publication of MOM’S CANCER by Abrams Books in 2006, and I expect we’ll do something to mark that. Actuarially, I have more future projects in mind than I have likely years left to do them, which is a nice position to be in.

Listing my influences would be a whole other interview. I grew up on newspaper comics and superhero comic books, so those are imprinted in my DNA. Charles Schulz, Walt Kelly, Milt Caniff, Alex Raymond, Winsor McCay, Cliff Sterrett, Jack Kirby, John Buscema, Neal Adams, Alex Toth. Too many.

I’m similarly hopeless recommending works to read, partly because I’ve become friends with so many cartoonists I’d hate to leave anyone out. I would encourage any cartoonist to read widely beyond comics. Read science and history, study Renaissance and Modern art. Cultivate other interests and then bring your enthusiasm for them into your comics. It will give you a unique style and voice. I’ve often joked that if you are the world’s foremost authority on collecting bottle caps, and you can create a comic that makes me care as much about bottle caps as you do, I will be your fan for life. Turn your weirdness into a strength, and you’ll be surprised how many like-minded weirdos you find.