CALVIN AND HOBBES - Serio Comics 36

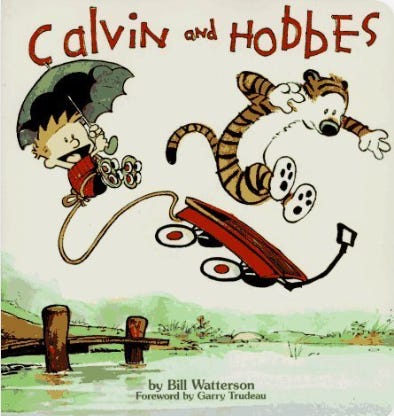

CALVIN AND HOBBES written and drawn by Bill Watterson, published by Andrews McMeel

Scholastic Book Fair

Is anyone else old enough to remember the Scholastic Book Fair in their schools?

I used my allowance back then to buy this 1987 Bill Watterson Calvin and Hobbes book.

As well as most of the rest of his oeuvre.

I remember very much wanting only these books.

Over any other kind of book.

Including prose novels.

And other comic books.

But it’s been a number of years since I went back and read this first one.

So here goes…

Bill Watterson’s Journey

Bill Watterson is an American cartoonist who authored the comic strip Calvin and Hobbes, which was syndicated for newspapers from 1985 to 1995.

Watterson drew his first cartoon at age eight, and spent much time in childhood alone, drawing and cartooning. This continued through his school years, during which time he discovered comic strips such as Walt Kelly's Pogo.

George Herriman's Krazy Kat.

And Charles M. Schulz's Peanuts.

Which subsequently inspired and influenced his desire to become a professional cartoonist.

After high school, Watterson attended Kenyon College, where he majored in political science. He had already decided on a career in cartooning, but he felt studying political science would help him move into editorial cartooning. He continued to develop his art skills, and during his sophomore year he re-created the painting of Michelangelo's Creation of Adam on the ceiling of his dormitory room. He also contributed cartoons to the college newspaper, some of which included the original "Spaceman Spiff" cartoons.

Later, when Watterson was creating names for the characters in his comic strip, he decided on Calvin (after the Protestant reformer John Calvin) and Hobbes (after the social philosopher Thomas Hobbes), allegedly as a "tip of the hat" to Kenyon's political science department. In The Complete Calvin and Hobbes, Watterson stated that Calvin was named for "a 16th-century theologian who believed in predestination".

And Hobbes for "a 17th-century philosopher with a dim view of human nature".

Watterson later became known for his negative views on comic syndication and licensing, his efforts to expand and elevate the newspaper comic as an art form, and his abrupt move back into private life after ending Calvin and Hobbes after 10 years.

“Certainly nothing like the character of Calvin that he later created”

Watterson’s parents recalled him as a “‘conservative child’” - imaginative…but certainly nothing like the character of Calvin that he later created.

So who was that character in this first CALVIN AND HOBBES book?

Calvin was a child whose crush on neighbor Susie was often projected as animosity.

He was a child who took enormous daredevil risks, despite the consequences.

He was a child who didn’t really ask for permission let alone forgiveness.

He was a child who was resigned to his generational fate of addiction to television.

He’s a child who had difficulty learning the value of and respecting the need to earn money.

He’s a child who almost always wanted to do what was most pleasurable.

He’s a child who was always looking for more freedom and less responsibility.

And he’s a child who seemed to think he knew the cost of growing up.

But that’s just one interpretation…

To quote The New Yorker’s Rivka Galchen in her review of Watterson’s first work since Calvin and Hobbes 2023 THE MYSTERIES…

An ongoing enchantment is at the heart of "Calvin and Hobbes." It's at the heart of "Don Quixote" and "Peter Pan," too. These are stories about difficult and not infrequently destructive characters who are lost in their own worlds. At the same time, these characters embody most of what is good: the gifts of play, of the inner life, of imagining something other than what is there. If "The Mysteries" is a fable, then its moral might be that, when we believe we've understood the mysteries, we are misunderstanding; when we think we've solved them and have moved on, that error can be our dissolution.

Foreword Backward

Yet this re-read was the first time I ever remember reading the foreword by Garry Trudeau of Doonesbury.

Let alone perhaps understanding it.

Trudeau seems to be saying that Watterson captures the immaturity of childhood. How a child’s word doesn’t mean anything. Because it’s constantly shifting. Along with their feelings. And therefore they do not feel they are lying.

Trudeau adds that some grown-ups try to regain what he calls this serendipity of youth, they attempt to retrieve the irretrievable.

But that the few who do are desperate cases.

Who end up in rehab and mental hospitals.

Whereas sensible adults merely enjoy Calvin and Hobbes and do not act it out.

Too Serious, Too Semiautobiographical Thoughts

My debut SHOULD WE BUY A GUN? is a semiautobiographical seriocomic.

I tend to sometimes enjoy including semiautobiography in my literary enthusiasms.

So I wanted to risk reflecting a bit seriously on the comic’s influence on me personally.

While re-reading CALVIN AND HOBBES I was struck by how much I identified with this child-man.

Back then as a child.

And even still today as a man.

While re-reading, I worried how the influence of this irreverence shaped my character.

And I wished I had heeded or could still do better heeding Trudeau’s warning to grow up…

Cynical-Realism Gen X Charm

And yet, there’s something quite charming about this Gen X cynically-realistic depiction of the risks of parenting.

And also some hints at the rewards as well.

Wattever Happened to Watterson

I had not looked into what happened to Watterson after he stopped making Calvin and Hobbes.

So I did some research.

And also watched the 2013 documentary.

I was surprised by what I found out.

There seemed to be two major ways of thinking about it.

The documentary celebrated Watterson’s run unabashedly.

But other accounts analyzed Watterson’s own ambivalence to show why we should maybe be ambivalent about his work too.

If you’re curious…

I collaged a depiction of the unabahsed celebration in captioned images from the documentary by Joel Allen Schroeder with an account of the ambivalence in words from an article by Nic Rowan.

It starts now below…

But has to be continued with a view entire message click if you’re reading in email.

Or you can click this Link here button to go the post in a web browser or the Substack app.

Enthusiasm vs. Ambivalence

“When Bill Watterson walked away from Calvin and Hobbes in 1995, he was exhausted. The comic strip had consumed ten years of his life, the latter half of which were spent fighting his syndicate for creative control and warring with himself as he fitfully came to realize that he had nothing left to say about a six-year-old boy and his stuffed tiger. And the decision couldn’t have come at a worse time: Calvin and Hobbes was at the height of its popularity. To quit then seemed like career suicide.

It was suicide, the intentional, ritualistic sort. Watterson wasn’t just done with daily newspaper cartoons; he was finished with public life. After his last Sunday strip ran on December 31 of that year, he retired to his home and resolved never again to publish cartoons. Watterson described the experience as a sort of death: ‘I had virtually no life beyond the drawing board,’ he said of the years leading up to the decision. ‘To switch off the job, I would’ve had to switch off my head.’

In the years since the strip’s end, Watterson has indicated that there was something false inherent to Calvin and Hobbes, some impurity either in his approach or encoded in the strip itself that made it impossible to continue in good faith.

‘I lost the conviction that I wanted to spend my life cartooning,’ he remembers realizing in 1991, four years before he ended the strip.

The trouble with Calvin and Hobbes started at the very beginning, when Watterson was a year out of college. In those days, he was nothing if not earnest. He was working at the Cincinnati Enquirer as a political cartoonist, a job he had scored through Jim Borgman, a school connection on the paper’s staff. (Borgman is better known now for illustrating Zits.) The job was a bad fit: Watterson had no feel for horse race politics. At Kenyon College, he had studied political science under the school’s resident Straussians, reading Plato, Machiavelli, Hobbes, and Locke—but decontextualized theories of political life did him little good in the 1980 presidential primaries, which he had been assigned to cover. Watterson recalls absentmindedly doodling George H.W. Bush in an editorial board meeting as the rest of the staff drilled the future vice president on Ronald Reagan’s fitness for office. He felt totally lost. Within a few months, he was fired.

Then came a long period of bitterness. Watterson moved back in with his parents and took a job designing layouts for a weekly free ad sheet which was handed out at his local grocery store. He received minimum wage and slaved in a windowless basement office. His boss shouted at him frequently. His car was in constant need of repair. During his lunch break, he read books in a cemetery. He did this job for four years.

And he developed a monomania that would become the force behind his life’s work. He had failed at politics. He could feel himself failing at advertising. There was only one other career he could envision, and it was in humor.

But there was nothing funny about how he achieved it. Calvin and Hobbes was conceived in desperation and executed in panic.

By the time Watterson secured syndication for the strip (it debuted in thirty-five newspapers), he had devised a system of work that he describes as ‘pathologically antisocial.’

His editor advised him at the outset not to quit his day job immediately; strips often fail within the first year, and it would be discouraging for him to leave one gig only to lose another. But Watterson didn’t listen. He decided that he would rather be destitute than ever do anything besides Calvin and Hobbes. As the years rolled on and the strip grew in its popularity, his wish was granted.

‘Work and home were so intermingled that I had no refuge from the strip when I needed a break,’ Watterson recalls. ‘Day or night, the work was always right there, and the book-publishing schedule was as relentless as the newspaper deadlines. Having certain perfectionist and maniacal tendencies, I was consumed by Calvin and Hobbes.’

By Watterson’s own admission, he cannot accurately recall a whole decade of his life because of his ‘Ahab-like obsession’ with his work. ‘The intensity of pushing the writing and drawing as far as my skills allowed was the whole point of doing it,’ he says. ‘I eliminated pretty much everything from my life that wasn’t the strip.’

While Watterson’s wife, Melissa Richmond, organized everything around him, he furthered his isolation, burrowing ever more deeply into the strip’s world. There was no other way, he believed, to keep its integrity absolute. ‘My approach was probably too crazy to sustain for a lifetime,’ he says, ‘but it let me draw the exact strip I wanted while it lasted.’

When crises arose, it often seemed like the end of the world. First, there was the fight with the syndicate. It looks like a piddling matter now, when few newspapers turn a profit, but in the Reagan era, there was still some money to be made in print media—particularly in licensing the rights to popular cartoons. Watterson wasn’t opposed to licensing in principle, but he felt that nearly all the merchandising proposals presented to him would devalue his strip of its artistic merit.

He fought with his syndicate for years and expressed his dissatisfaction with the business side of the comics industry in speeches, in interviews, and, eventually, in court. At last, he won a renegotiated contract and the right to draw bigger, more complex Sunday strips, something Watterson had wanted since he began.

The victory was pyrrhic. ‘For the last half of the strip, I had all the artistic freedom I ever wanted, I had sabbaticals, I had a good lead on deadlines, and I felt I was working at the peak of my talents,’ he says. But Watterson had designed a world for himself so self-contained that any disruption could mean its destruction: ‘I just knew it was time to go.’

This much became clear in the middle of the licensing fight. It took up so much of his energy that he lost his lead time on the strip and found himself in a situation where he was drawing practically every single comic on press night.

After a few weeks of this, he broke down. ‘I was in a black despair,’ he says. ‘I was absolutely frantic. I had to publish everything I thought of, no matter what it was, and I found that idea almost unbearable.’

His wife saw him spiraling out of control and drew up a schedule that helped him slowly, over the course of six months, rebuild his lead time.

Not long after, Watterson crashed his bike, bruised a rib, and broke a finger.

He was so afraid of losing his lead again that he propped his drawing board on his knees in his sickbed and drew anyway.

That freaked him out, too, and so gradually he scaled his life down to the point where nothing unpredictable could happen.

Even as he harnessed every waking second for Calvin and Hobbes, some malignant force within pushed him to dizzying heights of anxiety. ‘I would go through these cycles of despair and elation based on the perceived quality of the strip—things that I doubt anyone else could see in either direction,’ Watterson says. ‘It was all a bit manic.’

Needless to say, Watterson had no children throughout the entire run of Calvin and Hobbes.

He wasn’t particularly interested in that sort of thing, and, anyway, in his guarded world there was no time for children.

This is odd to consider, especially since the strip is putatively about childhood and family life, and its reputation rests largely on the fact that kids still love it.

For my own part, Calvin and Hobbes consumed much of my childhood, as I am sure is the case for many other people who came of age at the turn of the millennium.

But the attraction, I think, derived mainly from the fact Calvin thinks, speaks, and acts like no child in existence. Everything about his character is utterly alien to an actual six-year-old; yet his environment is so fully realized and the adults in his world so true to life that his own reality is almost completely convincing. To the clever child, however, it becomes clear quickly that in the mind of his creator, Calvin is a tiny adult surrounded by large adults, confined to the strictures of childhood only by accident of his age and size.

This is why the strip often appeals most to the lonely and unhappy, to children who do not think of themselves as such and to adults who are better thought of as children.

Watterson admits freely that he falls into that latter category. ‘Calvin reflects my adulthood more than my childhood,’ he says.

‘I suspect that most of us get old without growing up, and that inside every adult (sometimes not very far inside) is a bratty kid who wants everything his own way.’

Of course, Calvin and Hobbes aren’t the only characters who reflect Watterson. Calvin’s mom, his dad, Susie Derkins, Rosalyn the babysitter, even Moe the bully—they’re all Watterson’s creations; his own personality is present in all of them.

‘Together, they’re pretty much a transcript of my mental diary,’ he says.

‘I didn’t set out to do this, but that’s what came out, and frankly it’s pretty startling to reread these strips and see my personality exposed so plainly right there on paper. I meant to disguise that better.’

Watterson is right that he didn’t disguise himself very well, and the way his monomania practically screams off the page can be rather unsettling.

I have before me now the three-volume, complete Calvin and Hobbes, which, at twenty-three pounds, is the heaviest book ever to have appeared on the New York Times bestseller list. I have read it multiple times in its entirety.

For every delightful Sunday strip about dinosaurs or Spaceman Spiff or Calvin’s wagon careening into a pond as Hobbes covers his eyes in mock horror

There are five daily strips about the evils of television, the depravity of advertising, the sorry state of modern art, and, of course, the four last things: death, judgment, heaven, and hell—all placed in the mouth of six-year-old who with each passing year seems to become more cynical, more pissed-off, more bitter.

I can flip to almost any page in this set and find something that reveals its creator’s inner anguish. The most famous example—often cited by Watterson himself—is a Sunday strip that appeared in February 1991.

It is drawn almost entirely in black-and-white ink and depicts an argument between Calvin and his dad.

In the last panel, the only one drawn in color, Calvin’s dad says, ‘The problem is, you see everything in terms of black and white.’

Calvin replies: ‘SOMETIMES, THAT’S JUST THE WAY THINGS ARE.’

Watterson says that the strip was a ‘metaphor’ for the battle with his syndicate.

It is a blatant reference to Watterson’s own life, and anyone following Calvin and Hobbes closely would have picked up on it.

I could go on like this for pages, flipping back and forth at random through the entire collection.

But the point is, save for the first few months of the strip, which, for easily forgivable reasons, veer more toward lame, canned jokes, Calvin and Hobbes reads like a ten-year-long experiment in hysterical realism.

Fans often mistake these outbursts for philosophy (a characterization that Watterson vigorously resists), but the truth is much more mundane.

These are simply the natural thoughts of a man chained to his desk.

‘Comic strips are typically written in a certain amount of panic,’ Watterson sometimes reminds fans. ‘I just wrote what I thought about.’

What then to do when there is nothing left to think about?

Watterson compares ending Calvin and Hobbes to reaching the summit of a high mountain. He had ascended slowly, covering much rough ground, and when he had reached the crest of that lofty peak, he paused to survey his surroundings.

Anyone who has climbed a mountain knows exactly what happens in this moment: You look up and see nothing but pale blue sky. You look down, and the whole world is laid out before you, seemingly complete. In that rarified air, it is easy to imagine that there is nothing else beside.

People go crazy on mountaintops.

Which is exactly what happened to Watterson.

He had no desire to return whence he came.

And he couldn’t go any higher; no one can ascend into the air itself.

So he took his next best option.

He jumped.

Unpacking the Mashup

What’s most interesting to me about this article, quoted in full, by Nic Rowan of The American Conservative, mashed up and mixed with the captioned moments from the documentary by Joel Allen Schroeder for Amazon Prime.

Is how I both understand Nic’s relatively damning conservative reaction.

And not wanting to promote such a rebellious and libertine lifestyle.

But at the core I’m still an enthusiast of Calvin And Hobbes like Joel Allan Schroeder.

Watterson Became A Parent

We do know now that Bill Watterson did become a parent.

In the early 2000s, he and his wife, then in their forties, adopted a daughter who became, Watterson says, his first priority.

And fatherhood, it seems, altered the way he views his previous work.

When asked by a fan in 2005 if there is anything he would change if he were to restart Calvin and Hobbes now, Watterson laughed at the impossibility of such an idea and said, “Well, let’s just say that when I read the strip now, I see the work of a much younger man.”

Monomaniacal SHOULD WE BUY A GUN?

As you can see I can relate to Bill Watterson’s years-long mania for a project.

And I even put in an homage…

Thanks for reading! Here are some quotes that might inspire…

To endure five years of rejection to get a job requires either a faith in oneself that borders on delusion or a love of the work. I loved the work.

A real job is a job you hate.

It’s surprising how hard we’ll work when the work is done just for ourselves.